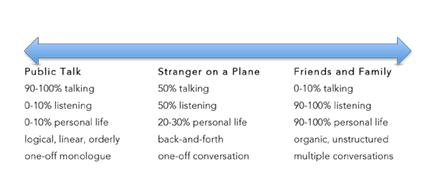

In the second scenario, we find ourselves talking to a stranger, whom we will never meet again. For example, in my work, I often find myself talking to the Uber driver or the person sitting next to me on the plane. In this scenario, the stranger and I will share the talking—it’s a 50-50% split. We go back-and-forth. I talk, and they talk. Here, the person still knows very little about my personal life, but they might have some clues as to the person I am. Am I polite to the flight attendant? Did I sit in the front seat or the back seat with the Uber driver? Did I offer to share my snacks? Here, I still have some control of the agenda and direction of the conversation, but so does the other person. As a result, we might flitter between talking about things that matter and things that don’t matter all that much—e.g., the weather, the sports scores, and what the traffic is like.

In the third scenario, which is the topic of this chapter, we are trying to talk to close friends and family, whom we might be stuck with for the rest of our lives. For example, in my work as a medical doctor, most of the doctors and nurses that I work with are non-believers. I also have close family members—an uncle, a cousin—who are non-believers. In this scenario, things are no longer so straightforward. On the one hand, we have multiple opportunities to have conversations. But on the other hand, if the conversation becomes unpleasant, things will be awkward between us every time that we have to see each other again. Another difficulty is that if we’ve already had a few conversations about things that matter—the environment, gun control, immigration, the gospel—and they don’t agree with us, then it’s highly unlikely that they will change their minds just because we bring the matter up again.

In this scenario, the nature of the conversation will be very organic. There is no logical presentation of ideas. Instead, the conversation evolves on its own accord. Furthermore, we may well find that the other person does almost 90-100% of the talking. We get to do only 0-10% of the talking! The ratio of talking versus listening is completely flipped from what it is to give a public talk. Conversely, they will know almost 100% of our personal life. Again, this is completely flipped from what it is when we give a public talk.

Why is this important? Because, as you probably know, the Ancient Greeks taught that there are three components to a message—logos (what I say), pathos (the way I make you feel), and ethos (how I live). When I give a public talk, there is a lot of logos and pathos, but little ethos. But when it comes to talking to close friends and family, ethos becomes a huge component in our message.

The Bible has similar insights. For example, in 1 Peter 3:1-2, it says that non-believing husbands can be “won over without words by the behavior of their wives, when they see the purity and reverence of [their] lives.”2 That is to say, in close personal relationships our ethos—the way we live—might be much more persuasive than our logos—what we say.

So we understand that there is a spectrum of engagements with non-believers. Giving a public talk is not the same as talking to a stranger on a plane; and talking to a stranger on a plane is not the same as talking to your roommate about Jesus. As a result, we need to be realistic in our expectations. For example, if we’re talking to a close friend, we probably will not be able to give a twenty-minute monologue. And that’s OK. We should not be comparing our evangelistic method with Billy Graham’s at Wembley Stadium. Nor to an Aaron Sorkin speech!

But even more, it also shows the disproportionately large part that ethos plays in personal evangelism. What we say is important. But the more closely someone knows us, the more they will be persuaded by our way of life than merely by what we can say.

2. Find creative ways to do hospitality

I grew up in Australia. My Asian parents never had roof-racks on their cars. That’s because Asian parents back then generally didn’t surf or go camping. So they had no need for roof-racks. So, as a child, I never noticed any roof-racks. But now that I’m all grown up, I wanted to buy roof-racks for my car. And that’s when I noticed that roof-racks are everywhere. There are grey ones. There are black ones. There are rounded ones. And there are oblong ones. How did I not notice all of this before?

It’s the same with hospitality. For most of my Christian life I hadn’t noticed hospitality in the Bible. But now that I go looking for it, hospitality is everywhere in the Bible. The word “hospitality” occurs in Acts, Romans, 1 Timothy, Hebrews, 1 Peter, and 3 John. In other words, almost every New Testament writer uses it.

But the idea of hospitality goes beyond the word occurrence. It’s there when Zacchaeus welcomes Jesus into his home with joy (Luke 19:5-6). Or when Levi throws a banquet for Jesus and invites his tax-collecting friends (Luke 5:29). It’s there when Lydia invites Paul and his entourage to her home (Acts 16:15). Or when the jailer takes Paul and Silas to his home for a meal (Acts 16:34). Interestingly, in many of these examples, it’s the non-believer who is hospitable to the believer!

But what’s the big deal about hospitality? You see, hospitality provides the spaces where conversations occur. In almost every other area of life it’s difficult to have a conversation of any weighty matter. Sometimes it’s because it’s inconvenient—they have a train to catch. Sometimes it’s inappropriate—they should be working and not talking to you. Sometimes it goes against social etiquette—it’s not the time nor place to talk. But the whole point of a meal together is to talk. The great irony of eating together is that it isn’t about the food. It’s about connecting. Relating. And talking.

There are several things that we can take away from this. First, if a non-believer invites us to their home for a meal, we should make it a top priority to go. In Luke 7, we have the story of a woman anointing and washing Jesus’ feet with her hair, tears, and perfume. This is a major moment in the story. But it also distracts us from another key moment in the story. And it’s this: When Simon the Pharisee invited Jesus to his home for dinner, Jesus went! Similarly, in Luke 14:1, Jesus went to the house of a prominent Pharisee.