1.2. Premise 2

What, then, about premise 2? Is it more plausibly true than false? Although premise 2 might appear at first to be controversial, what’s really awkward for the atheist is that premise 2 is logically equivalent to the typical atheist response to the contingency argument. (Two statements are logically equivalent if it’s impossible for one to be true and the other one false. They stand or fall together.) So what does the atheist almost always say in response to the contingency argument? He typically asserts the following:

A. If atheism is true, the universe has no explanation of its existence.

Since, on atheism, the universe is the ultimate reality, it just exists as a brute fact. But that is logically equivalent to saying this:

B. If the universe has an explanation of its existence, then atheism is not true.

So you can’t affirm (A) and deny (B). But (B) is virtually synonymous with premise 2! (Just compare them.) So by saying that, given atheism, the universe has no explanation, the atheist is implicitly admitting premise 2: if the universe does have an explanation, then God exists.

Besides that, premise 2 is very plausible in its own right. For think of what the universe is: all of space-time reality, including all matter and energy. It follows that if the universe has a cause of its existence, that cause must be a non-physical, immaterial being beyond space and time. Now there are only two sorts of things that could fit that description: either an abstract object like a number or else an unembodied mind. But abstract objects can’t cause anything. That’s part of what it means to be abstract. The number seven, for example, can’t cause any effects. So if there is a cause of the universe, it must be a transcendent, unembodied Mind, which is what Christians understand God to be.

1.3. Premise 3

Premise 3 is undeniable for any sincere seeker after truth. Obviously the universe exists!

1.4. Conclusion

From these three premises it follows that God exists. Now if God exists, the explanation of God’s existence lies in the necessity of his own nature, since, as even the atheist recognizes, it’s impossible for God to have a cause. So if this argument is successful, it proves the existence of a necessary, uncaused, timeless, spaceless, immaterial, personal Creator of the universe. This is truly astonishing!

1.5. Dawkins’s Response

So what does Dawkins have to say in response to this argument? Nothing! Just look at pages 77–78 of his book where you’d expect this argument to come up. All you’ll find is a brief discussion of some watered down versions of Thomas Aquinas’ arguments, but nothing about the argument from contingency. This is quite remarkable since the argument from contingency is one of the most famous arguments for God’s existence and is defended today by philosophers such as Alexander Pruss, Timothy O’Connor, Stephen Davis, Robert Koons, and Richard Swinburne, to name a few.4

2. The Kalam Cosmological Argument Based on the Beginning of the Universe

Here’s a different version of the cosmological argument, which I have called the kalam cosmological argument in honor of its medieval Muslim proponents (kalam is the Arabic word for theology):

- Everything that begins to exist has a cause.

- The universe began to exist.

- Therefore, the universe has a cause.

Once we reach the conclusion that the universe has a cause, we can then analyze what properties such a cause must have and assess its theological significance.

Now again the argument is logically ironclad. So the only question is whether the two premises are more plausibly true than their denials.

2.1. Premise 1

Premise 1 seems obviously true—at the least, more so than its negation. First, it’s rooted in the necessary truth that something cannot come into being uncaused from nothing. To suggest that things could just pop into being uncaused out of nothing is literally worse than magic. Second, if things really could come into being uncaused out of nothing, then it’s inexplicable why just anything and everything do not come into existence uncaused from nothing. Third, premise 1 is constantly confirmed in our experience as we see things that begin to exist being brought about by prior causes.

2.2. Premise 2

Premise 2 can be supported both by philosophical argument and by scientific evidence. The philosophical arguments aim to show that there cannot have been an infinite regress of past events. In other words, the series of past events must be finite and have had a beginning. Some of these arguments try to show that it is impossible for an actually infinite number of things to exist; therefore, an infinite number of past events cannot exist. Others try to show that an actually infinite series of past events could never elapse; since the series of past events has obviously elapsed, the number of past events must be finite.

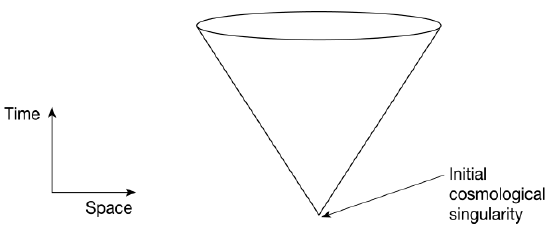

The scientific evidence for premise 2 is based on the expansion of the universe and the thermodynamic properties of the universe. According to the Big Bang model of the origin of the universe, physical space and time, along with all the matter and energy in the universe, came into being at a point in the past about 13.7 billion years ago (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Geometrical Representation of Standard Model Space-Time. Space and time begin at the initial cosmological singularity, before which literally nothing exists.

What makes the Big Bang so amazing is that it represents the origin of the universe from literally nothing. As the physicist P. C. W. Davies explains, “the coming into being of the universe, as discussed in modern science . . . is not just a matter of imposing some sort of organization . . . upon a previous incoherent state, but literally the coming-into-being of all physical things from nothing.”5

Of course, cosmologists have proposed alternative theories over the years to try to avoid this absolute beginning, but none of these theories has commended itself to the scientific community as more plausible than the Big Bang theory. In fact, in 2003 Arvind Borde, Alan Guth, and Alexander Vilenkin proved that any universe that is, on average, in a state of cosmic expansion cannot be eternal in the past but must have an absolute beginning. Their proof holds regardless of the physical description of the very early universe, which still eludes scientists, and applies even to any wider multiverse of which our universe might be thought to be a part. Vilenkin pulls no punches:

It is said that an argument is what convinces reasonable men and a proof is what it takes to convince even an unreasonable man. With the proof now in place, cosmologists can no longer hide behind the possibility of a past-eternal universe. There is no escape, they have to face the problem of a cosmic beginning.6

Moreover, in addition to the evidence based on the expansion of the universe, we have thermodynamic evidence for the beginning of the universe. The Second Law of Thermodynamics predicts that in a finite amount of time, the universe will grind down to a cold, dark, dilute, and lifeless state. But if it has already existed for infinite time, the universe should now be in such a desolate condition. Scientists have therefore concluded that the universe must have begun to exist a finite time ago and is now in the process of winding down.

2.3. Conclusion

It follows logically from the two premises that the universe has a cause. The prominent New Atheist philosopher Daniel Dennett agrees that the universe has a cause, but he thinks that the cause of the universe is itself! Yes, he’s serious. In what he calls “the ultimate boot-strapping trick,” he claims that the universe created itself.7

Dennett’s view is plainly nonsense. Notice that he’s not saying that the universe is self-caused in the sense that it has always existed. No, Dennett agrees that the universe had an absolute beginning but claims that the universe brought itself into being. But this is clearly impossible, for in order to create itself, the universe would have to already exist. It would have to exist before it existed! Dennett’s view is thus logically incoherent. The cause of the universe must therefore be a transcendent cause beyond the universe.

So what properties must such a cause of the universe possess? As the cause of space and time, it must transcend space and time and therefore exist timelessly and non-spatially (at least without the universe). This transcendent cause must therefore be changeless and immaterial because (1) anything that is timeless must also be unchanging and (2) anything that is changeless must be non-physical and immaterial since material things are constantly changing at the molecular and atomic levels. Such a cause must be without a beginning and uncaused, at least in the sense of lacking any prior causal conditions, since there cannot be an infinite regress of causes. Ockham’s Razor (the principle that states that we should not multiply causes beyond necessity) will shave away any other causes since only one cause is required to explain the effect. This entity must be unimaginably powerful, if not omnipotent, since it created the universe without any material cause.

Finally, and most remarkably, such a transcendent first cause is plausibly personal. We’ve already seen in our discussion of the argument from contingency that the personhood of the first cause of the universe is implied by its timelessness and immateriality. The only entities that can possess such properties are either minds or abstract objects like numbers. But abstract objects don’t stand in causal relations. Therefore, the transcendent cause of the origin of the universe must be an unembodied mind.8

Moreover, the personhood of the first cause is also implied since the origin of an effect with a beginning is a cause without a beginning. We’ve seen that the beginning of the universe was the effect of a first cause. By the nature of the case that cause cannot have a beginning of its existence or any prior cause. It just exists changelessly without beginning, and a finite time ago it brought the universe into existence. Now this is very peculiar. The cause is in some sense eternal and yet the effect that it produced is not eternal but began to exist a finite time ago. How can this happen? If the sufficient conditions for the effect are eternal, then why isn’t the effect also eternal? How can a first event come to exist if the cause of that event exists changelessly and eternally? How can the cause exist without its effect?

There seems to be only one way out of this dilemma, and that’s to say that the cause of the universe’s beginning is a personal agent who freely chooses to create a universe in time. Philosophers call this type of causation “agent causation,” and because the agent is free, he can initiate new effects by freely bringing about conditions that were not previously present. Thus, a finite time ago a Creator could have freely brought the world into being at that moment. In this way, the Creator could exist changelessly and eternally but choose to create the world in time. (By “choose” one need not mean that the Creator changes his mind about the decision to create, but that he freely and eternally intends to create a world with a beginning.) By exercising his causal power, he therefore brings it about that a world with a beginning comes to exist.9 So the cause is eternal, but the effect is not. In this way, then, it is possible for the temporal universe to have come to exist from an eternal cause: through the free will of a personal Creator.

So on the basis of an analysis of the argument’s conclusion, we may therefore infer that a personal Creator of the universe exists who is uncaused, without beginning, changeless, immaterial, timeless, spaceless, and unimaginably powerful.

On the contemporary scene philosophers such as Stuart Hackett, David Oderberg, Mark Nowacki, and I have defended the kalam cosmological argument.10